The Man and The Crowd (1928) Photography, Film, and Fate

“Make films about the people, they said”, Jean-Luc Godard once quipped, “but The Crowd had already been made, so why remake it?” Gideon Leek rewatches King Vidor’s classic, in which a young man with big dreams moves to New York City and becomes an identical cog who learns to love the machine of modernity.

October 9, 2024

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Film still of Johnny Sims (played by James Murray) from The Crowd (1928) — Source.

In an 1861 lecture before the Tremont Temple in Boston, the American abolitionist Frederick Douglass spoke on the democratic potential of the daguerreotype. “Men of all conditions may see themselves as others see them. What was once the exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now within reach of all. The humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week, may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and even royalty, with all its precious treasures, could purchase fifty years ago.”1 A more half-empty perspective was expressed by the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. “With the daguerreotype everyone will be able to have their portrait taken—formerly it was only the prominent; and at the same time everything is being done to make us all look exactly the same—so that we shall only need one portrait.”2 Douglass hoped photography would make everyone equal; Kierkegaard worried it would make everyone the same. In one of the key late silent films, King Vidor’s The Crowd (1928), it is Kierkegaard’s prophecy that comes true — if not for the daguerreotype, then for its technological successor, the motion picture.3

Vidor’s 1928 film tells the story of Johnny Sims, born on the Fourth of July at the dawn of a new century. The Crowd is a reflection on the United States in the 1920s, the America of Warren G. Harding’s “return to normalcy” in the wake of World War I and the Spanish Flu. Sims is a man who is meant to be America — its hopes, its dreams, its destiny. At twelve, he “recited poetry, played the piano and sang in a choir” (the intertitle notes: “So did Lincoln and Washington”). About this chosen son of a small town, his father swears, “There is a little man the world is going to hear from.” Johnny held these great expectations close, saying, in response to his schoolmates’ more concrete dreams (preacher, cowboy): “My daddy says I’m going to be something big.”

Boy matures into man with the drop of a title card: “When Johnny was twenty-one he became one of the seven million who believe New York depends on them.” We see Sims idealistic and smiling, proudly resting his monogrammed luggage on a ferry railing, gazing fondly at the city. A man walks over, frumpled, dejected, burnt out, no luggage: this is clearly a local. He leans on the railing and says to Sims, “You’ve gotta be good in that town if you want to beat the crowd.” Still smiling, the young man replies: “Maybe but I just want an opportunity.” The man rolls his eyes in disbelief. Soon the camera, along with Sims, gets lost in a crowd.

The Rise of the Deindividual

If The Crowd shares the preoccupation with modernity, individualism, and anonymity that Baudelaire found in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Man of the Crowd” (1840), its medium offered a new set of representational techniques for exploring early twentieth-century urbanization’s effects on the individual. Prior to film and photography, ownership of paintings was one of the only ways to possess a visual monument of individuality. This is my face, this is my house, this is my grandmother, this is my finery. With their paintings, the wealthy could make a case for themselves as above replacement by invoking status, the past glory of ancestors, or, more obliquely, their incipient rise as a person of taste. Collections of commissioned paintings were both proof of one’s wealth and, just as often, a display of other riches. As John Berger notes in the documentary series Ways of Seeing, “To paint a thing, and put it on a canvas, is not unlike buying it.”4 Not only did the owners of paintings possess the majesty of history, but also, in a more solipsistic vein, the beauty of their own (albeit sometimes tastefully exaggerated) possessions, lands, trinkets, delicacies, even other paintings.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

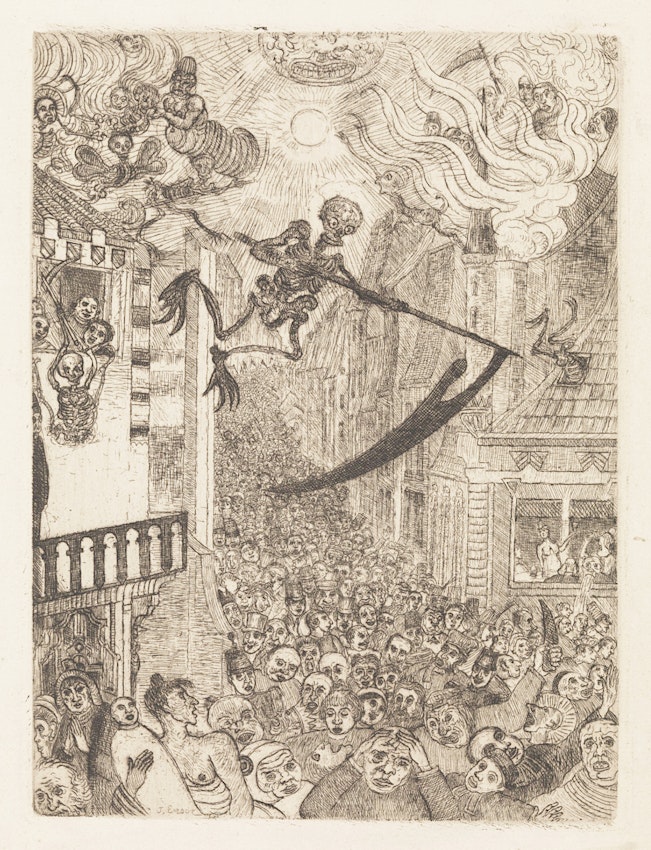

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.James Ensor, Death Chasing the Flock of Mortals, 1896, an etching that some scholars argue was inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Man of the Crowd” — Source.

By the last decades of the nineteenth century, novel photographic technologies changed this equation. Suddenly, new segments of the population could potentially afford to preserve themselves on film. There is often, to contemporary eyes, a strange solitude in these images; the studio portrait excels at highlighting difference and personality, and, contra Kierkegaard, few people look “exactly the same”. Like a commissioned painting, photographic portraits were often made against a backdrop, set apart from daily life — the individual becomes the image’s sole focus. Take, for example, this blind man, or this combed-down office worker, or this “wily Yankee” whittler. The advent of cinema, however, saw the individual represented differently. Less dependent on exposure times or controlled lighting, early documentary film could take to the streets, and the individual, in turn, was often demoted from center stage to a sameness of smudges, Ezra Pound’s “petals on a wet black bough”.5 See this lovely 1902 static shot by F. S. Armitage of ice skaters in Central Park, the swirling bodies at the New York City Fish Market in a 1903 Edison short, the parallel focus on a mass of indistinguishable immigrants arriving at Ellis Island that same year, or the nearly identical policeman in a 1904 American Mutoscope and Biograph Company film, who lead nearly identical businessmen across the newly opened Williamsburg Bridge backed by an array of identical American flags flapping in unison. Both the photograph and the moving picture democratized the image, but their creators had different approaches to the individual during the latter form’s early days.

The twentieth century saw mass global homogenization followed by a confluent fetishization of the individual. Film, the century’s dominant art form, underwent the same development. The fin-de-siècle period that spawned these early films of faceless crowds was a time of mass cultural assimilation, as people moved from rural areas to cities at increasing speeds. These early documentaries stand in stark contrast to what film is best known for: mythologizing the importance of heroic individuality. In the following decades, the popular film format would coalesce in a rather different image: not the crowd shot, but the close-up. The Crowd falls somewhere between these two chapters of cinematic history — pitting the techniques of documentary against narrative conventions, mass anonymity against individual striving. And in this collision of modes, poor Johnny Sims doesn’t stand a chance.

King Vidor’s Spiritual Integrity

One of the key filmmakers of the twentieth century, King Vidor directed his first Hollywood project, The Turn in the Road (1919), at age twenty-five and his last Hollywood film, Solomon and Sheba (1959), at sixty-five. In the intervening forty years, he made an astounding fifty-four narrative films. He worked with everyone from ZaSu Pitts to Audrey Hepburn, from Gary Cooper to Dino De Laurentis, from Lillian Gish to Ayn Rand, and inspired directors from Orson Welles to Billy Wilder to Jean Luc-Godard. In 1929, he directed Hallelujah, the first major studio film with an all-Black cast, and, after Victor Fleming pulled out to start filming Gone with the Wind, Vidor filled in to direct the Kansas scenes of The Wizard of Oz.6 In 1979, he received an honorary Oscar for “incomparable achievements”. (The Crowd, in turn, was nominated in multiple categories at the first Academy Awards in 1929.)

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Publicity shot of Edward Cronjager (left) and King Vidor (right) on the set of Bird of Paradise (1932) — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Publicity shot of King Vidor (left) and Eleanor Boardman (right) on the set of The Crowd (1928) — Source.

The breadth of Vidor’s work was vast, but many of his most enduring films, including The Crowd, were provocative studies of the American working class. In his slice of tenement life Street Scene (1931), Kropotkin epic Our Daily Bread (1934), and mill worker melodrama Stella Dallas (1937), Vidor explored the lifestyles of the poor and anonymous. A devoted Christian Scientist and, beginning in the 1940s, a staunch anti-communist, Vidor’s private beliefs were not always flush with the leftward lean of his films.7

The march of man, as I see it, is not from the cradle to the grave. It is instead, from the animal or physical to the spiritual. The airplane, the atom bomb, radio, radar, television are all evidences of the urge to overcome the limitations of the physical in favor of the freedom of the spirit. Man, whether he is conscious of it or not, knows deep inside that he has a definite upward mission to perform during the time of his life span.8

A strange sentiment to hear from the director of The Crowd, with its critique of the gross individual burden of American Exceptionalism, but, as two of Vidor’s finest critics put it: “He accepted widely divergent, even opposite, moral attitudes as spiritual integrity.”9

In the early twenties, Vidor issued a bizarre statement of principles, stating his belief that “the motion picture carries a message to humanity”, swearing not to “cause fright, suggest fear, glorify mischief, condone cruelty or extenuate malice” and promising to “never to picture evil or wrong, except to prove the fallacy of its lure.”10 Even at the time, his actions did not always live up to his ideals. Vidor later recalled: “I might have been stupid enough in my first few pictures to put out a creed that I wouldn't make pictures with violence or sex. . . . It was an advertisement, you know. . . . Right after it came out in the paper, I got arrested for playing poker in a sixty-cent game. The headlines were pretty awful.”11 Whatever the contradictions of his philosophy, Vidor’s films brought the suffering of underrepresented populations to the screen. History remembers The Crowd not 1949’s The Fountainhead (a look down at the masses from the other end of the class spectrum: “You see those people down there? You know what they think of architecture?”).12 As Godard quipped in a moment of socialist pique: “Make films about the people, they said; but The Crowd had already been made, so why remake it?”13 And that’s not even to mention its technical feats, which bestow the story of Sims’ fall with vertiginous visuals.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Lobby card advertising The Crowd (1928) — Source.

The Mise-en-Scène of Sameness

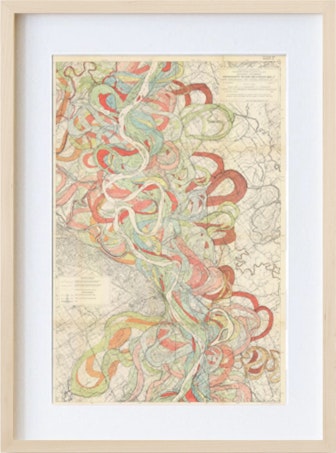

After the ferry scene of city-bound Sims, a montage of New York evokes the earliest moving pictures. Vidor, who had directed some documentaries of his own, all lost, recalls aiming for a “documentary flavor” in The Crowd, and it is the same collective perspective this montage takes on.14 Instead of Sims’ view, the camera is seeing from the eyes of a collective, anonymous body. First, it tracks hundreds of people, many dressed the same, on their way to an enormous variety of very similar places, then moves outward to show trains, the capillaries that pump people through the pulsing city, and outward again to the billowing smoke and the boats in the harbor. The sequence was filmed anonymously too. Vidor recalls: “For scenes of the sidewalks of New York, we designed a pushcart perambulator carrying what appeared to be inoffensive packing boxes. Inside the hollowed-out boxes there was room for one small-sized cameraman and one silent camera. We pushed this contraption from the Bowery to Times Square.”15

As the camera leaves the street and returns to the skyscrapers, panning over them slowly, carefully, Vidor switches back from the crowd’s documentary perspective to Sims’ more expressionist one — a calculated effect that he employs throughout the film.16 The authors of King Vidor, American (1988) explain this use of the contrasting styles: “Each has its primary domain—documentary shifting to expressionism when John’s private oppression fills the world.”17 The Crowd’s documentary view of New York ends as we zoom into Sims’ personal pain. In the middle of a row of skyscrapers, the camera starts to spin, tilting up to reveal dozens of identical windows, and begins to slither up the building. The crawl slows and the camera rights itself horizontally and enters a vast open room filled with identical desks. The zoom continues, showing so many indistinct functionaries, accomplishing inseparable tasks, and, among them Johnny Sims, the boy who had every opportunity, who was heir to Lincoln and Washington. Instead of being something big, he has become something very small indeed — an identical exponent, a person with no need for a portrait. Kierkegaard may have been right.

Film clip from The Crowd. The shot was achieved by cameraman Henry Sharp gliding his camera across a skyscraper model that was positioned horizontally on the studio floor — Source.

As a technical feat, the transition is masterful, involving several invisible dissolves, multiple miniatures, a photograph placed in a window, and a great many desks.18 “This camera maneuver was designed to illustrate our theme”, that Johnny Sims was just “one of the mob, one of the crowd” nothing more (for Johnny, Vidor uses the word “hero” in scare quotes).19 There are numerous other clever ways that Vidor shows Sims’ sameness. The hero proceeds through the stages of life haunted by his indistinction. Before a date with the woman who will become his wife, other women, for other men, are dispensed like gumballs from a revolving door. When Sims waits in the hospital for the birth of his first child, Vidor places him in a forced-perspective hallway, with the doorways becoming smaller and smaller, “to give the impression that many husbands were also going through the same suspense and agony.”20 (Initially, Vidor wanted to perfect the illusion with persons of short stature stationed at the smaller doors, but, perhaps wisely, abandoned this idea.21) However, it was not just Vidor’s mise-en-scènes that made Johnny such an anyman.22 Vidor literally picked the lead, James Murray, out of a group of extras.23 Previously, Murray starred as a doorman.24

Regarding this tension between the individual and the undistinguished masses, philosopher Gilles Deleuze discussed Vidor’s work in his influential 1983 study Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. “In the whole realist pan of his work King Vidor was able to set up great global syntheses, moving from the collectivity to the individual and from the individual to the collectivity.” In Vidor, Deleuze also finds an alternate structure, in which the new situation is no different than the old one: “such that the individual no longer knows what to do and at best finds himself in the same situation once more: the American nightmare in The Crowd.”25 Johnny Sims moves to a bigger pond, hoping to grow into a bigger fish, and all he finds is a smaller view of himself.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Film still from The Crowd (1928) — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Film still from The Crowd (1928) — Source.

Pantomiming Modernity

When he was fifteen, a few years before the age at which Johnny Sims left home, King Vidor saw A Trip to the Moon in the Grand Opera House of Galveston, Texas.26 Soon after, he began working as a ticket taker, and, later, a projectionist, at Galveston’s Globe Theater, a venue located behind the pianos in a working music store.27 Projection in those days was dangerous — Vidor describes the lingering threat of “flaming hell” — but the movies were worth the risk. Of the early films they ran at the Globe in Galveston, those shot by the French pantomimist Max Linder made the biggest impression on young King. “In every story I remember, he was looking for something—a misplaced umbrella, a lost wallet, a stolen pair of pants. Also in every film he invariably pulled the chamber pot from under the bed, removed its cover, looked inside for the lost article, held his nose, and replaced the cover while facing the camera with a horrified expression.”28 From a projection booth off the South Coast of Texas, Vidor “absorbed all the clichés of French pantomime: the thumbnail pushed violently out from the upper front teeth to denote contempt; an open palm waggled diagonally by the chin to indicate a curse; a finger pointed upward followed by the head resting on the hands, held palm to palm meaning, ‘He is upstairs sleeping.’”29

The pantomime figures of Vidor’s youth return in The Crowd. Early in the film, we find Sims on a date, gazing down at the swarming sidewalk from a streetcar. He draws his future wife’s attention to the crowd, exclaiming, “The poor boobs . . . all in the same rut!” Sims, destined for size and significance, doesn’t see himself in the working men. Suddenly, he spots a true nonpareil. Someone who really does stand out from the crowd: a juggling clown, wearing a sandwich board, advertising shoes. Sims’ face lights up with the joy of schadenfreude. Giggling, he says, “The poor sap! And I bet his father thought he would be President!” Later, after a great deal of melodrama — alcohol, affairs, the death of a child — an abject, jobless Sims also finds gainful employment as a sandwich board clown, wearing a sign that reads: “I am always happy because I eat at Schneider’s Grill”. His father thought he would be the president too.

“When the picture was finished, we had a difficult time deciding on an ending”, recalls Vidor. “We made seven of them, and tried out each one at sneak previews in small towns.” They ultimately whittled it down to two: there was a happy ending, featuring a Christmas reunion and parental affirmation, and the “realistic” ending that Vidor ultimately chose: Sims in the audience of a variety theater, one face among many, laughing merrily at “Sleight O’Hand, the Magic Cleaner”, a fellow juggling clown. “Since he managed to enjoy life, and therefore conquer it, in this simple and inoffensive way”, explained the director, “the camera moved back and up to lose him in the crowd as it had found him.”30 Vidor suggests that Sims has accepted his lot in life. He’s not sneering at the clowns anymore; he has finally found his place in the crowd. Yet there is another way to read the ending: Johnny Sims has simply seized upon a new oneiric strand of the American dream: show business. Which, far more than the presidency, was the secret hope of the twentieth-century individual. His eyes are once again as wide as when he gazed upon New York at the beginning of his career. “I’m going to be something big”, you can almost hear him say.

Film clip from the ending of The Crowd, in which Johnny Sims finds himself comfortable among the masses of a variety theater — Source.

Gideon Leek is a writer based in Brooklyn. He has contributed essays and reviews to Liberties, The Village Voice, Los Angeles Review of Books, Cleveland Review of Books, The Millions, Screen Slate, and Harvard Review.