Our Mortal Waltz The Dance of Death Across Centuries

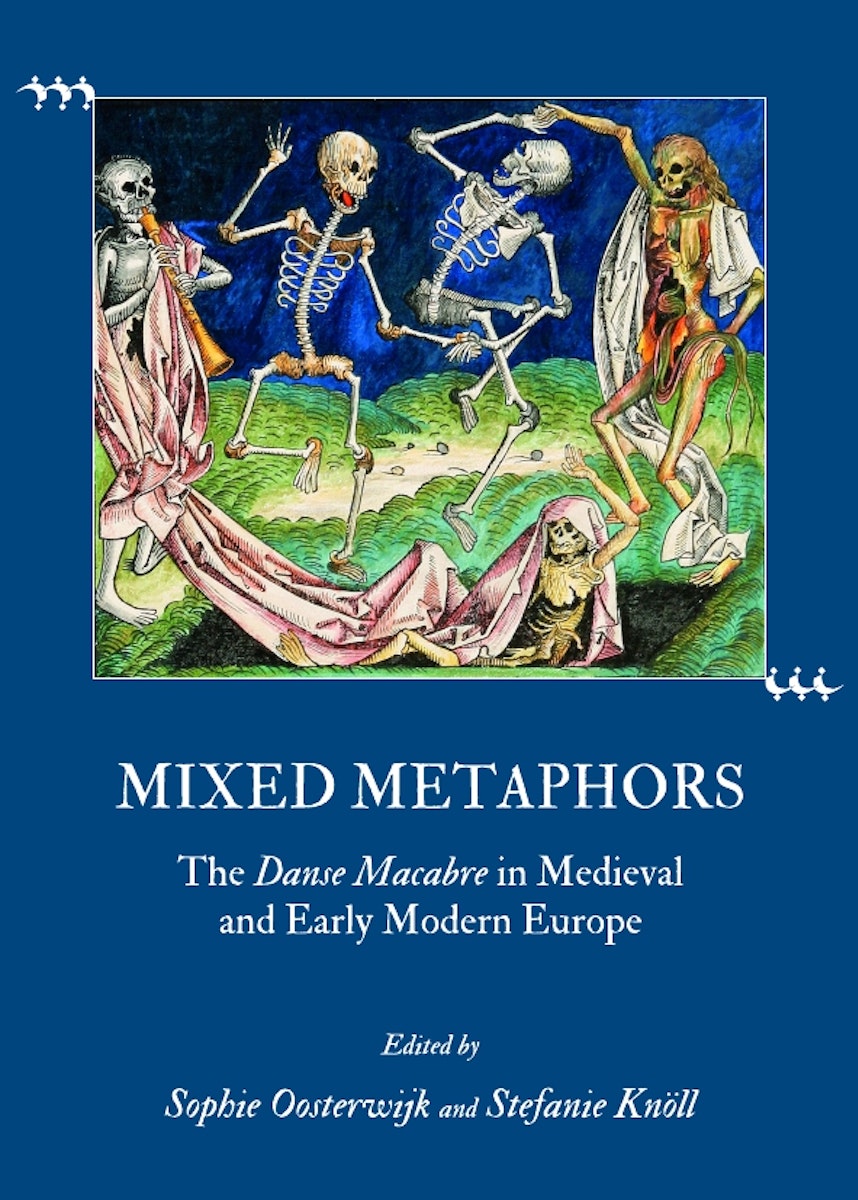

The sight of a skeletal corpse rarely inspires a rollicking jig. Yet for more than half a millennium, the dance of death in European visual art has imagined a tango between the quick and the dead. Allison C. Meier tracks the motif’s evolution across history, discovering how — through times of disease, war, and economic inequality — printmaking offered a means to both critique social ills and reflect upon new forms of human devastation.

July 11, 2024

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Percy John Delf Smith, Death Intoxicated, 1919 — Source.

In the trenches on the Western Front of World War I, British artist Percy Smith experienced firsthand the new violence of modern warfare. While serving as a gunner with the Royal Marine Artillery, he covertly sketched the shattered trees and ravaged earth between the trenches, as well as the bodies of soldiers left where they fell in this no-man’s-land. Later, Smith made a portfolio of seven etchings, repurposing a centuries-old visual allegory to convey the horrors of the battlefield. In each scene of The Dance of Death, 1914–1918, a skeletal figure wrapped in a shroud lurks among the soldiers, marching alongside their columns and pondering the wrecked landscape of trenches and barbed wire. By the final print, “Death Intoxicated”, death is exultant in the bloodshed. With bony arms raised, it casts off its shroud and dances across the battlefield, where men in gas masks with bayonets charge toward their fate.1

Smith was far from the first artist to use the dance of death to account for the toll of mass casualties.2 This specific allegory of mortality dates back to medieval Europe. More than a memento mori, a form that reminds an individual of their impending expiration, the dance of dance often stresses the mass threats to life in a particular era. This is perhaps why printmaking, which allows for faster and wider distribution than painting in response to unfolding events, has frequently been a preferred medium for the dance. Across more than half a millennium, artists have turned to the mass production possibilities of printing to rapidly share updated versions of this ghoulish waltz that reflect the harrowing circumstances of their historical moment.

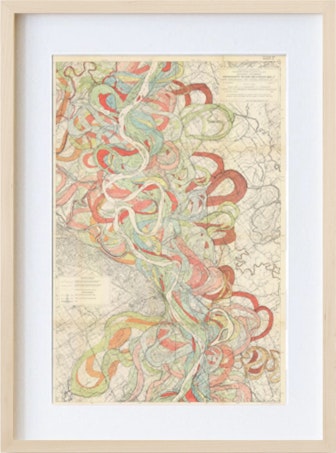

Scholars usually cite a 1424–25 mural painted in the Cimetière des Innocents in Paris as the earliest known visual depiction of the dance of death, although the allegory had previously appeared in medieval plays. It was painted in the alcoves of the cemetery’s charnel house, but the cemetery of the fifteenth century was not the somber graveyard we might imagine.3 A lively market was once situated abreast the Cimetière des Innocents; both life and death passed daily by the graves and the painted skeletons. The thin borders between this marketplace and cemetery echoed the mortal chain that would become the dance’s leitmotif. In the mural, cadaverous skeletons and living people were shown hand in hand, representing all classes — emperors and shepherds, clergy and shopkeepers — accompanied by didactic verse. This scene encouraged the viewer to be pious with what time remained, and to consider the salvation of their soul. Class, status, wealth, and success, it seemed to say, will all be laid waste in the end. There is a subversiveness in figuring death as a dance: taking a collective rhythmic movement usually associated with joy — happy skeletons are later shown wielding musical instruments — and using it as a reminder that every person is processing toward the same end.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Xylograph engraving, sometimes attributed to Pierre Le Rouge, based on the mural at the Cimetière des Innocents, from a 1490 edition of Guy Marchant’s La danse macabre nouvelle — Source.

The Cimetière des Innocents’ dance of death was destroyed in 1669 as part of a road-widening project, yet it endured as a cultural force through a number of fifteenth-century books that circulated replications of the mural across Europe. These disseminated images inspired further imitations, both textual and visual. In 1485, Parisian book printer Guy Marchant created the especially influential La danse macabre nouvelle, pairing xylographs — a type of wood engraving — with text based on the cemetery mural’s inscriptions. A rare copy of the 1485 edition, held by the Bibliothèque municipale de Grenoble in France, depicts characters including a cardinal, king, doctor, and even a child. They are all forced to dance together by corpses, whose skin still clings around their sardonic grins, carrying shovels for the grave. The figures representing different classes and trades as well as “La Mort” (Death) are given dialogue in verse. In one exchange, La Mort speaks to La Maistre (an astrologer) and says: “Master, neither your gazing at the heavens, / Nor all your knowledge, / Can slow the arrival of death. Astrology has no power here”. La Maistre woefully replies: “Neither my knowledge nor my degrees / Can give me resources / For now I deeply regret / Dying in confusion”.4 La danse macabre nouvelle, however, was not the first publication to portray the dance of death: the Morgan Library in New York has a 1430–35 book of hours from France with illuminated ornate illustrations of the dance of death as part of its florid marginalia, and Heidelberg University Library in Germany has a dance of death circa 1455–58 printed as a hand-colored block book.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Dance of death images from Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. germ. 438, 1455–58 — Source.

As publishing and printing advanced, so, too, did the unstoppable dance of death. The motif’s entwinement with techniques for copying and replicating images creates a morbid parallel to the rise of visual reproduction in Europe. The dance has no beginning or end — for death is one of life’s only constants — and watching it transform on the printed page across centuries gives the sense that we are looking at one continuous chain in these images: the rich and the poor and their dance partner, death, reappear over and over again. Yet even printers and their presses get folded into the dance of death tableaux, as if the preservation offered by texts and images is just a temporary way of staving off the inevitable. The earliest depiction of a printing shop and press is thought to be a 1499 dance of death published in Lyon by Mathias Huss, which survives (for now) in two known copies.5 Amid the usual conga line of doomed souls, we find a scene of three animated corpses pulling away the bookseller, pressman, and typesetter from their tasks. (The enmeshment of death and printing innovation continued into 1790, when an edition of Marchant’s work translated into Latin became one of the earliest books to have a title page that includes a printer, publisher, and date.)

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.A dance of death scene published by Mathias Huss in La Grant Danse Macabre (1499), which is thought to be the earliest visual depiction of a printing shop and press — Source.

Unlike the procession of flat medieval figures, by the sixteenth century, the dance of death had gained depth and settings that better represented contemporary Europe, with all its inequalities and imbalances of power. The impact of the Italian Renaissance on the rise of perspective and realism in art over the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries is well known, influencing representational forms in all media. This included printmaking, where a new interest in naturalism — conveyed through detailed shading and the delicate carving of woodblocks — led to a dance that was more graphic and complex. Major economic growth, where wealth generated by increasingly international commerce could soar but also plummet as financial crashes punctuated the decades, left many behind, with class divisions even more visible as population booms led to burgeoning cities where the poor and the rich often lived closer together than before. The dance of death could highlight the vanity of the rich, and the futility of the system that elevated their station: posh and pauper alike meet their reaper at the end.

German artist and printmaker Hans Holbein the Younger reimagined the dance with a new spirit of social commentary that responded to this age. His dance of death, made with blockcutter Hans Lützelburger between 1523 and 1526, changed the way the motif would be interpreted by the artists who followed. In these scenes, the living and dead are no longer dancing together, and instead, death intrudes on the activities of daily life. Death is a mischievous skeleton that taps the clergyman from behind his pulpit with an hourglass in hand, dances in a jester costume before the queen, and pounds the drum in the noblewoman’s path. Holbein’s dance was not published until 1538 in Lyon — following Lützelburger’s own death twelve years before — as Les simulachres & historiees faces de la mort. Its swift popularity led to reprints, copies, and imitations in the decades that followed, such as an early seventeenth-century dance of death by German engraver Eberhard Kieser. He added decorative flourishes and borders of cut flowers that further emphasized the ephemerality of life.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Woodblock prints of “The Abbot”, “The Lady”, and “The Nobleman” from Hans Holbein’s The Dance of Death (1523–25) — Source.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.While engraving requires specialized skill and knowledge, the rise of etching allowed artists to draw directly with needles on a wax- or varnish-covered plate, which was incised with acid before printing. This new accessibility allowed the dance of death to take on novel, visceral forms that meditated on the epidemics, war, and short life expectancies that made the medieval theme continually relevant. Italian printmaker Stefano della Bella’s 1648 “Death Carrying off a Child”, for example — part of his The Five Deaths series of etchings — employed the Cimetière des Innocents in Paris as its setting. By this time, there were print shops on the ground floor of the charnel house; the reproduction of texts and images kept its own pace alongside the turnover of life in the graveyard. He personified death in these baroque images as ruthless and terrifying; the gaunt corpse with the child on its back opens its mouth in a horrific scream as life and death go on without pause in the vividly depicted cemetery behind them.

By the end of the eighteenth century, there was a return to some of the satirical humor found in Holbein. Significantly, death in this era rarely appears as a fetid corpse and instead is usually a clean skeleton; the actual mortal decay of the human body is distant from these dances. Freund heins Erscheinungen in Holbeins Manier by Johann Karl August Musäus, illustrated by Johann Rudolf Schellenberg and printed by Heinrich Steiner in Switzerland in 1785, has etchings imbued with a sharp wit — in one scene, for example, death is dressed in the finery of a fashionable lady, complete with coiffed hair, leading a baffled gentleman away. Although Holbein is referenced in the book’s title, the publication focuses less on the dynamics of social class and more on the inevitability of death. In scenes of contemporary Enlightenment life, death stalks into the collector’s wunderkammer, where a crocodile hangs overhead, as well as a scholar’s study, toppling his shelf of books, while the explosion of a newly invented hot air balloon brings its riders down to earth.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.The most playful dance to be printed in the nineteenth century was English artist Thomas Rowlandson’s illustrations for The English Dance of Death (1816). The aquatints colorfully depict death as a cartoonish character, startling people with unfortunate and often wryly depicted fates. People line up at the apothecary for cures brewed by a skeleton with “slow poison”; an anatomist is stopped from dissecting a corpse by death itself barging in. As with many of the medieval depictions of death’s dance, these images are accompanied with verse, here written by the poet William Combe. Take, for example, a scene of people enjoying a snowy day of ice skating sent into chaos by a gliding skeleton: “On the frail Ice, the whirring Skate / Becomes an Instrument of Fate”.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.“On the frail Ice, the whirring Skate / Becomes an Instrument of Fate”, coloured aquatint after Thomas Rowlandson, 1816 — Source.

By this time, there was a wide diversity of available printmaking techniques in Europe that further increased the speed of production and dissemination. Artists employed such techniques to react in the moment to crises, including the spread of disease. The 1830s cholera outbreaks in Europe conjured, for many, stories of the medieval plague and resurrected, again, the dance of death. German artist Alfred Rethel’s 1851 engraving, “Death the Strangler”, for example, depicts cholera’s disruption of the 1831 carnival festivities in Paris. A robed skeleton plays a fiddle made of bones while surrounded by the dead at a masked ball, evoking the folly of how the upper echelon of society thought it would be spared from this supposed disease of the poor.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Alfred Rethel, Death the Strangler, The First Outbreak of Cholera at a Masked Ball in Paris, 1831 — Source.

Cholera also haunts Nuremberg artist Tobias Weiss’ Ein Moderner Totentanz (ca. 1894), a series of twenty etchings, in which a skeleton driving a carriage heaped with coffins of epidemic victims is joined by train derailments, automobile wrecks, and specific catastrophes, like the 1893 sinking of the HMS Victoria — part of a ship collision that killed 358 people. Here, too, death continues its indomitable foxtrot of calamity.

Entering the twentieth century, French artist Marcel Roux took up the dance to channel his feelings about the decadence and decay of the modern world from a perspective of devout Catholicism. His Danse Macabre (1904–5) portfolio of fifteen etchings is frequently nightmarish, recalling the moody tones of Goya more than Holbein’s prankish skeletons. In dark, densely drawn lines, death laughs alongside the drinkers at a cabaret, drapes its hand on the back of a man watching a carnival performance, and plays piano with a woman in a dim parlor, before Jesus triumphantly crushes its bones beneath his feet.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Frontispiece by Marcel Roux for his portfolio of etchings Danse Macabre (1904–5) — Source.

Faith and divine help are absent, however, in many of the early twentieth-century versions of the motif, which stare down the horrors of World War I. German artist Walter Draesner’s Ein Totentanz (1922) employed prints of paper-cut silhouettes, rendering death as part of an unforgiving landscape. His ghastly skeletal figure is hiding everywhere — below a broken train bridge, in a pond holding up a flower to two children — and is a colossus, not bothering to hide, taking down airplanes with a tap of its finger and tearing apart the masts of ships with its hands.

The dance of death would reappear in printmaking throughout the twentieth century, with artists inspired by events analogous to those that fueled the motif in the past, reproducing visions of mortality in numerous copies when it seemed like death itself was inescapable. German artist Käthe Kollwitz’s Death series of eight crayon lithographs (1934–37) was created in the wake of the Nazi rise to power. These prints show death alternately offering a welcome release and a harrowing final embrace to women and children. American artist Mabel Dwight’s lithograph “Dance of Death” (1933) was made the same year Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. It depicts a puppet performance where figures including Mussolini, Hitler, Uncle Sam, and others represent countries that will soon be part of the global conflict. The audience has one solitary member: a skeleton who wears a gas mask. Although far removed from the medieval dances, this work similarly asserts how, in these grasps for mortal dominance, there will ultimately be only one victor: death.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.

Scroll through the whole page to download all images before printing.Käthe Kollwitz, Call of Death, 1937 — Source.

Allison C. Meier is a Brooklyn-based writer, editor, and researcher. Her book Grave was published last year by Bloomsbury as part of the Object Lessons book series. She is the editor of Fine Books & Collections magazine and has bylines in the New York Times, The Art Newspaper, Raw Vision Magazine, CityLab, National Geographic, Smithsonian, and many other publications. She moonlights as a cemetery tour guide.