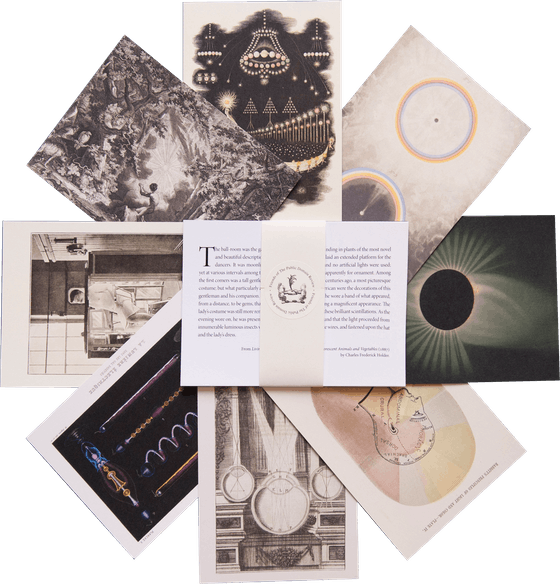

Edwin D. Babbitt’s Principles of Light and Color (1878)

While chromotherapy — the correction of physical and psychic imbalances through exposure to antidotal hues — is now widely dismissed as pseudoscience, its influence is everywhere in our LED-lit world. If you’ve ever worn blue light–blocking glasses, made your smartphone screen grayscale to lessen its addictive pull, dabbled with “Seasonal Color Analysis” (a system to match clothing to complexion), or gazed into a full-spectrum SAD lamp to cure the winter blues, you have engaged with the legacy of a notably late-nineteenth-century tenet. Chromotherapy bundled religious instincts with feel-good optical optimism. Stained glass no longer merely symbolized the sacred. It became a portal to the promise of renewed life through science.

Edwin D. Babbitt’s Principles of Light and Color (1878) was not the first influential book on modern chromotherapy — see, for example, this 1876 treatise on blue light written on blue paper — but it was certainly the most verbose. The first few chapters of Babbit’s six-hundred-page tome read like a somewhat sober primer on color theory and analysis, not altogether distinct from Munsell’s Atlas (1915), Vanderpoel’s Problems (1902), or Gartside’s Essay (1808). It is only after a section on the harmonic laws of the universe, which supposedly structure everything from the Milky Way to visual art to human health and the behavior of subatomic particles, that we come across hundreds of pages of chromotherapeutic case studies.

Despite its cutting-edge façade, Principles of Light and Color revolves around a positively premodern principle that has gripped the medical imagination since before the time of Avicenna: things that look alike are curatively entwined. But whereas the doctrine of signatures held that sympathetic substances were inscribed in similar ways by the hand of God, here divine order gets refashioned as spectroscopy. Red light stimulates the flow of arterial blood, for example, because both are red, and much of Babbitt’s system reads like medieval humoral theory dressed up in chromatic garbs. Since their energy fields are already ruddy, redheaded patients, those with “very rubicund countenance”, and residents of “French Insane Asylums” do better with calming blue light. Yellow rays work wonders on bilious and constipated bodies. It is no coincidence that magnesium carbonate and castor oil are also yellow, for these medicines’ efficacy is derived from harmonic vibrations on the molecular level. (It truly is vibes all the way down.)

But there is also a kind of secularization of sun worship, too, in these medical recommendations. “It may readily be seen why cereals and fruits, growing, as they do, above ground and drinking in the refined elements of the sunlight so freely, constitute a higher grade of food or food-medicines than the roots, tubers, and bulbs . . . which grow underground.” A reader gradually gets the sense that Babbitt wishes we could photosynthesize directly and cut out the vegetal middlemen. Perhaps this will one day be possible, but in the meantime, the author offers healthful alternatives. He is a proponent of solariums, and believes that objects can be charged with “odic light” — an ethereal, invisible force that saturates the universe. From here, it is a short leap to his theory of “chromo-mentalism”, which holds that psychic phenomena can be explained as a capacity to perceive “higher colors”. This line of thought quickly refracts into gender essentialism: because women are less rational than men, and reason occurs via “slow and coarse ethers”, their feminine intuition “can move on the wings of lightning”. Principles of Light and Color concludes with an image borrowed from Plato’s allegory of the cave: “In passing this book over to the world, I would say that it will be grief indeed if, by my writings, I shall ever mislead any of my dear fellow-beings, for they are already quite enough befogged with darkness and superstition, and on the other hand it will be a joy unspeakable if I can guide many upward into higher and holier light.” Did Babbitt suspect that he was trafficking in shadows?

It would be too black-and-white to dismiss Babbitt as a chromophilic quack operating in prismatic isolation. Chromotherapy was once a widespread practice. At the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, Charles Féré tinted the panes of hysterics’ cells with violet glass; shell-shocked soldiers were placed into James Turrell–like color wards to cool their nerves during World War I; the American colonel Dinshah P. Ghadiali invented the Spectro-Chrome in 1920, which promised to cure excessive sexual craving by applying magenta and purple light to the breasts and genitals. These seeming advances in modern medicine took place against the backdrop of a pigment panic. Contemporary research on color blindness revealed that individuals perceived the environment in radically different ways, while the frenzy for new aniline dyes, and a public desire for novel tones like mauve and magenta, terrified scientists such as Milton Bradley, who described an early version of visual pollution. “He feared that manufacturers were disseminating the synthetic dyes pouring out of industrial chemistry labs so quickly and haphazardly that the visual environment had become littered with discordant arrangements”, writes Nicholas Gaskill. If an artist’s chosen palette can make or break her composition, and Day-Glo advertisements overburden a cityscape’s visual temperament, is it so outlandish to assume that the colors we absorb might have some effect on our soul and body?

Sep 17, 2024