Fantastic Planet: The Microscopy Album of Marinus Pieter Filbri (1887–88)

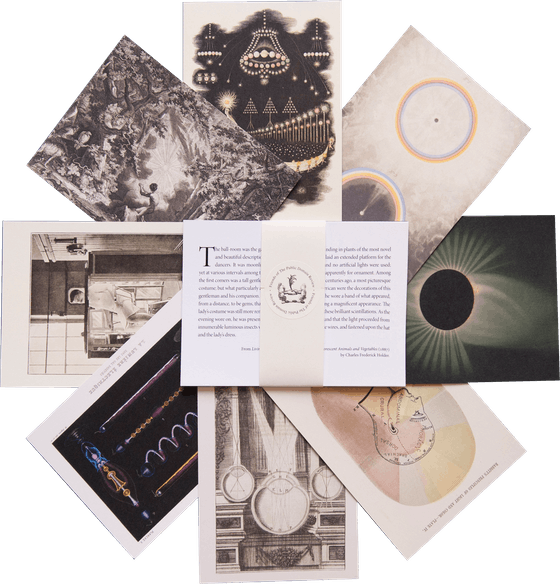

Toward the beginning of this album of photographs belonging to Marinus Pieter Filbri, there is a series of shots of the phases of the moon; closing it out, a glimpse through the gauze of an insect’s wing, magnified eighty times its normal size. Intentionally or not, this juxtaposition draws a visual parallel between the unimaginable scale of celestial objects and the invisibly small realm of the microscopic, as if to suggest that both, in the end, are equally alien.

The first third or so of the album is a mishmash of images — planetary bodies, cartes-de-visite of Sicilian bandits, a decapitated giraffe rider — that seem largely to be photographic reproductions (photos of photos) made by Filbri and combined into a scrapbook of sorts. It is this strange blend, at any rate, that serves as a bizarre prelude to the main content of the album: the micrographs.

Little is known about the album’s compiler, an amateur photographer whose position at the University of Utrecht’s physics laboratory may have first sparked an interest in plumbing the depths of the microcosmos. The Rijksmuseum credits Filbri himself with the micrographs his album contains, but Filbri also names other scientists in his inscriptions — suggesting that some were perhaps copies or collaborations. Whoever the creator, these images come to isolate and dramatize the minuscule geometries of the world around us: the curlicue of a moth’s antenna, the menacing dagger of a honeybee’s stinger, the architectural gridding of a fly’s eyeball.

The explorations of unseen worlds recall the work of Filbri’s countryman Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, who had pioneered the discipline of microscopy two centuries prior (though the curious magnifying properties of polished crystals and water flasks had been observed since ancient times). A haberdasher and fabric merchant by trade, van Leeuwenhoek’s lenscraft hobbyism would lead to his discovery of what he called “little animals” — forms of life too small to be seen with the naked eye. In his day, the singular novelty of van Leeuwenhoek’s experiments was such that the amateur scientist’s house was overrun by curious visitors eager to see what he had in store for them, whether the thrashing tails of spermatozoa or the coursing of blood through an eel. Filbri, who had previously lived in van Leeuwenhoek’s native Delft and worked in a scientific instruments factory before acquiring his university post, owned three original versions of his predecessor’s microscopes. By Filbri’s time, of course, microscopes had ceased to be luxury objects whose optical mechanism was a jealously guarded secret and become standard, industrially produced staples of the research laboratory.

The otherworldly allure of these images stems at least in part from the great effort involved in their success. Anyone who has ever fiddled and futzed with a microscope’s focus knobs in a biology class knows the tricksy fugitivity of achieving clear images at such a scale — how easily they dissolve into light and blur if the lens is set too close or too far from the specimen. “At the limits of optical microscope resolution it becomes difficult to distinguish real contours from illusions produced by the interaction of light with objects”, writes art historian James Elkins of the phantasmagoria at the other end of the eyepiece. In their quest to understand the natural world, the microscopists of Filbri’s day were faced with numerous challenges — “the Becke effect, diffraction patterns, chromatic aberration, astigmatism, and spherical aberration” — that made getting a clear and definitive view of certain specimens all but impossible. And yet, as Elkins notes, “some nineteenth-century microscopists achieved results no twentieth-century light microscope has bettered, and some twentieth-century electron microscope studies have failed to resolve issues raised by light microscopists.”

The peculiar and illusion-prone nature of microscopic images puts them at what Elkins calls “the end of representation” — a category into which, in another evocation of the macrocosm-microcosm relationship, he also places images produced by telescopes. Indeed, it’s tempting to see in some of these photos not the magnified versions of the Earth’s inhabitants but the contours and atmospheres of celestial bodies, an effect heightened by the circular framing. One picture of a fly’s head, for instance, conjures the moon traversing the sun during an eclipse, while shots of crystalized acids appear like the crater-pocked surface of a remote and alien planet. At the same time as these micrographs attempt to make legible the worlds within our world, they produce a contradictory sentiment in the viewer: that what we are seeing is so strange, so unfamiliar that it can only be coming to us from some cold corner of the outer universe.

Stinger of a honey bee, magnified 25 times

Feather of a hummingbird, magnified 25 times

Head of a mosquito, magnified 25 times

Swim leg of a backswimmer, magnified 25 times

Scale of a perch, magnified 25 times

Head of a moth, magnified 90 times

Antenna of a moth, magnified 30 times

Antenna of a June beetle, magnified 25 times

Wing of a fly, magnified 30 times

Wing of a mosquito, magnified 25 times

Shell of an insect, magnified 25 times

Leg of an insect, magnified 25 times

Boric acid crystals, magnified 35 times

Water sting, magnified 25 times

Diatoms, magnified 170 times

Mahogany, magnified 60 times

Diatoms, magnified 190 times

Mahogany, magnified 60 times

Diatoms, magnified 50 times

Young shellfish, magnified 50 times

Fly’s eye, magnified 170 times

Scale of a butterfly wing, magnified 350 times

Young starfish, magnified 25 times

Scale of a sole, magnified 25 times

Piece of a spine, magnified 25 times

Sole scale, magnified 25 times

Mahogany, magnified 60 times

Flies eye, magnified 60 times

Head of a fly, magnified 25 times

Scale of a perch, magnified 40 times

Diatoms, magnified 60 times

Diatoms, magnified 190 times

Sodium chloride, magnified 60 times

Dec 3, 2024